Let History Be Your (Fallible) Guide

A digression on historical inevitabilities and contingent facts

Life is full of luck - both good and bad. So is history. But on a personal level, we can say that luck favors the prepared, while historical luck seems to have a far more limited range from bad things, to worse ones. Why? And, at the end, what does this have to do with AI?

Contingency and happenstance, for the worse.

In this section, I will go on an extended digression outside my area of expertise - three cheers for epistemic trespassing! The central claim here, that international affairs and the course of nations are often wildly contingent on tiny events, isn’t, from what I understand, particularly controversial among historians. A few examples from the past century will illustrate.

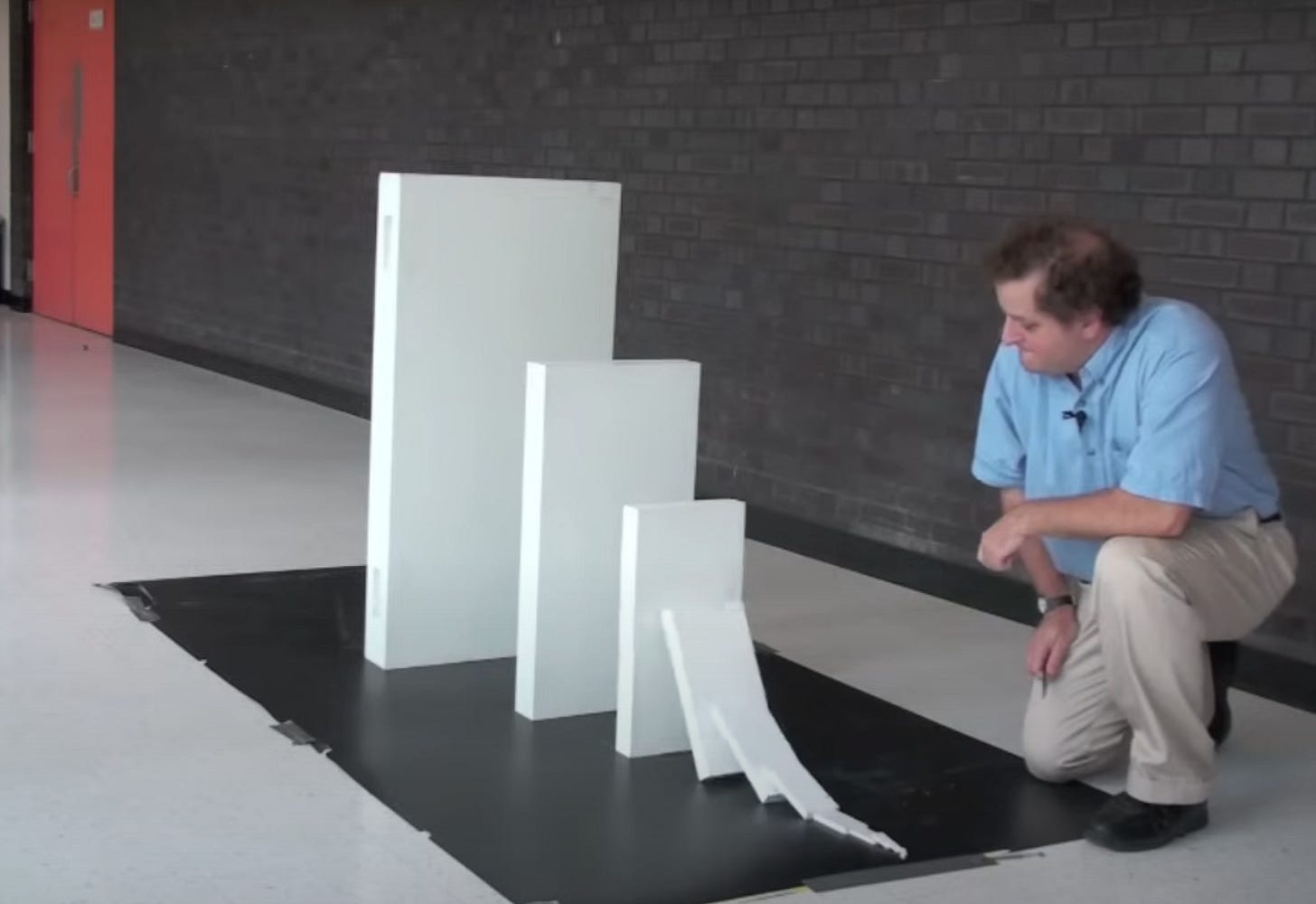

The proximal reason World War One started was a fluke assassination, and the almost comedic happenstance in that killing alone could make the point. But the way in which it spiraled out of control reinforces the contingency of the war. If Austria-Hungary had punished Serbia diplomatically instead of declaring war, the dominoes would have stopped there, and the war have been avoided. Of course, it seems plausible that the complex alliance system made it inevitable that some event would cause the entire web of secret treaties and public alliances to explode into a regional war. But if Germany didn't back Austria-Hungary, it could have remained a small war in the Balkans. And even after that point, if the UK had stayed out of the war, or if Russia had stayed neutral, Germany would have had a rapid victory, instead of horrific years of trench warfare. If America hadn’t joined, of course, the war would have dragged on even longer, perhaps tilting the balance the other way. The actual outcome was a reasonable course of action on each country’s part, but the outcome was contingent, if leaders had made different decisions.

Moving beyond the war itself, Woodrow Wilson was pushing hard to ensure the peace was permanent and fair, not punitive. Unfortunately, he (uncharacteristically) didn’t push back against France and Britain in Versailles when they demanded reparations to crush Germany economically. Why? Because Wilson had contracted Spanish flu. Pandemics may have been inevitable, but the co-occurence of the war made the disease far more deadly, and Woodrow Wilson’s inability to mediate at Versailles was just unlucky.

Of course, the proximate reason World War Two happened was a combination of German political pressures due to economic issues - the ones that Wilson wanted to prevent - and the emergence of a populist dictator. And economic crises give rise to populists, but in Germany, the specific dictator made a difference. If Hitler had gotten into art school, he wouldn’t have become a politician. If he had been among those killed at the Odeonsplatz during the beer hall putsch, or if he had escaped and gone into hiding, or if, as he said he was considering, he had committed suicide rather than be captured. But he was captured and put on public trial, where he was given a platform to deliver speeches that were widely reported. The lead judge was sympathetic, but he was still found guilty of treason - which carried a death penalty. Instead, he was given a short sentence and paroled early right into political conditions that allowed him to split the vote, take over, and launch a war. I won’t continue, but suffice it to say that World War II was no less full of similarly contingent factors.

Complex Systems Don’t Improve By Accident

As the heading says, it seems that humans build things that are at best resilient. Nassim Nicholas Taleb talks a lot about building antifragile things, but many of the things he discusses humans building are better described as well hedged. Open source software is easier to patch, so it’s in some sense robust to software bugs. Financial portfolios can be profitable in extreme situations, at the cost of normal performance, which makes them anti-correlated, but not strengthened by adversity. That is, a “barbell” portfolio doesn’t improve itself due to market drops, it just profits (only) in extreme situations.

But there are human things Taleb talks about that are truly antifragile - our bodies. Muscles develop and become stronger when overused, and the immune system learns adaptively from infections. Similarly, markets undergo creative destruction, as I discussed in the previous post, and cities grow organically and arguably work better when not centrally planned, at least outside of Singapore - and they tend to rebuild well. The running theme seems to be that unplanned systems that undergo stresses develop the ability to use those stresses, rather than to be degraded by them. Planned systems tend to be designed with withstand stresses, rather than depend on them.

When I asked ChatGPT to brainstorm counterexamples, it chose artificial “Biosphere” ecology projects, which utilize natural resilience, cybersecurity frameworks, which use testing to iteratively identify and address failure modes, and lean manufacturing systems, which are adaptable. The first isn’t really a counterexample, since it’s using natural systems, but the second and third are injecting a learning component into the failure cycle, which seems like it does address this problem explicitly. That is, as the section title suggests, human-designed complex systems don’t improve by accident.

This seems to explain why most surprises are bad ones - there is a fundamental asymmetry between catastrophes and efflorescences / eucatastrophes. So to complete the implied syllogism, history is driven by contingent and surprising events, and surprising events are bad, hence history is bad. Obviously, this isn’t true - but why is it wrong?

My answer is that the stories of history are the surprising events, but the trend in history is not. News, as we should know by know, systematically distorts our perception of the world. But, at least as commonly taught and learned, so does history! Our history classes focus on the big events, namely, wars, revolutions, and similar. That means it covers the more surprising positive developments - the renaissance, the industrial revolution, and the founding of modern democracy. Some of these are positive, but even then, a lot of the focus is on the negatives. I looked at the curriculum for AP World History, and until we get to globalization, every positive seems offset by a negative. Even for obviously positive developments, the curriculum is sure to mention all the negatives - remember, agriculture and modernity led to overpopulation! (Even though the feared overpopulation never, um, actually happened.)

What’s Going On When Nothing’s Going On?

Yes, Rome fell, but more people lived through the Pax Romana than lived when the Empire collapsed. The contingent parts are, at least arguably, less common and less impactful on the median person than the boring ones. The boring parts of history are that people lived their lives, mostly survived, had children, and on average, each generation improved things slightly for succeeding generations.

What was happening this whole time? Slow cultural and technological development. And this seems far less contingent - not in the details, or the exact speed, but in the direction.

And I will ague that this was more or less continuous. I won’t go into the topic here, but part of the popular conception of the fall of the Roman Empire being a step backwards is, in my view, mistaken. Not because it was not tragic, but because the intellectual tradition prevalent in Rome was stagnant in several ways. It took a serious rethinking of the nature of mathematics and science in order to enable much later developments. Even though it’s very likely that counterfactual innovation was slowed by the centuries of disorder following the fall of the empire, I doubt it was the case that humanity could have moved forward without many conceptual innovations and reconceptualizations that occurred during the so-called dark ages.

But progress is not linear. Not all developments are positive, and much innovation is a result of, or a contributing factor in, wars - not just who wins them, but the fighting itself. Despite this, most scientific and technological advances seem to be closer to inevitable discoveries than to accidents. And the implication is that the flourishing we have seen in recent centuries was in a sense inevitable.

I should note that there is a counterpoint, in regions or cultures that stagnated historically despite having access to similar knowledge or resources.

Conclusion

At this point, I’ll pivot back to the broader questions raised by and possibly addressed by this discussion - specifically, about technological risks.

If technological development is mostly inevitable, it paves the way for Bostrom’s Vulnerable World - if technological advances are roughly fixed in sequence, and the consequences follow, then the question of whether humanity is doomed by future technology is unknown, but not avoidable. Thankfully, history provides mechanistic models for specific dynamics, and gives forecasters useful base rates generally - it is far from an infallible guide.

But even then, there is a question about the dynamics of how technologies evolve. And that leads us into a question of whether to embrace a fatalistic model like Aschenbrenner’s view that we must race into AI. This follows naturally; prior to his conclusions in situational awareness he laid out the inevitable technological risk model in a 2020 paper. His more recent and very public views about needing to race to ASI are a result of that model - because, as the paper concludes, the best chance we have to get through the sequential but dangerous ASI phase is to race through the time of perils, and take the chance that we emerge safely on the other side.

The alternative is something more like Vitalik Buterin’s defensive accelerationism, which makes a slightly different assumption - that even if tech progress overall is a sequential tech tree, different parts can happen in different sequences. And if, as he suggests, there are places where defensive technologies can change these dynamics, the relative rate of investment into technologies seems to be a choice.

Of course, both options require some degree of coordination and cooperation, which will bring us back to our topic, and the issues I’ve been waiting to discuss about how cooperation relates to ASI. In the coming posts, we can finally get to the key question raised here; can cooperation be the key to navigating this technological landscape, or are we bound by historical inevitabilities?