So far on the blog, I omitted a critical part of cooperation: the goal. That is, people cooperate to do something, and what that thing is is kind-of central to any questions about why, whether, and how people cooperate. So we’re going to talk about what people want, what they value, and what they actually do. (And yes, those are all different.) That means we’re taking a break from cooperation to focus on individuals for this post. After this post, we’ll stop talking about individuals and get back to talking about cooperation, specifically, about how individuals and their preferences create conflict, and why most people’s preferences make it possible and even preferable to avoid conflict.

But before we get there, we should note that there are some special problems when an individual’s motivations are incoherent or poorly understood. At the same time, incoherence and lack of focus doesn’t mean that there isn’t any preference. In fact, even though people may not always be sure about what they want, they usually know what they like, or at least what they think they like. And if there are things they like, they spend a lot of time and energy getting it, whatever it may be. But not everything that people choose is what they want, much less what they believe is valuable.

Non-Satiation, Needs, Wants, and Superstimuli

Humans evolved in a much smaller world than we live in today. They were far more limited than most of us by their need for food, their ability to travel or communicate, and their ability to change their environment. Thankfully, those limitations are being solved, and a growing portion of humanity is facing new limits - ones that give a much greater level of freedom than our ancestors had. We have abundant food, nearly unlimited ability to communicate, and, increasingly, not only robust shelter from wind and rain, but even heating, air conditioning, and humidity controls. People can, on the whole, get what they always wanted. Then, of course, they want more.

Non-Satiation

Can people ever have enough? Economists, and cynics, often assume that the answer is no. If that’s true, if satiation is impossible, then the only reason people might not buy something is if they prefer other things, or they don’t have enough money. The economic non-satiation means that if they are offered more for free, they will always say yes. Always. Clearly, this assumption is unreasonable.

But before criticizing, I should note that assumptions are used for good reasons. Sometimes they make the math easier, and other times they guarantee that there is a solution in a given economic model. Non-satiation is a useful assumption for the second reason. For example, if we have a simple economic model where Bob grows apples, and Dave buys apples. If Bob grows 10 apples, but Dave gets satiated after 5, and won’t buy more, there is no price that Bob can charge to sell all his apples. Bob might not mind this, but it turns out it really annoys economists when they try to solve for a variable and find out there is no answer.

Let’s assume you win a contest - as many blueberries as you want, for one day only. After you get the first million blueberries, you’ve certainly eaten all that you can, and you’re giving them away to friends. The truck pulls up and offers you more blueberries, and maybe you take a second million, but if nothing else, at some point there’s nowhere to put all the blueberries - it’s not like you just pile up the extra blueberries forever - at some point, it would get much too messy.

There is a point at which we’ve had enough, and we stop wanting blueberries. Even if we’d be happy having a dozen trucks full of them, we’d want to stop somewhere. But economists, unlike blueberry contest winners, use simplified models, which means they make assumptions. And in this fanciful case of unlimited blueberries, the assumption can look silly. (For an amusing example of exactly what too many blueberries would lead to, see Anders Sandberg’s 2018 paper, “Blueberry Earth,” which features phrases which seem more at home in a Douglas Adams or Terry Pratchett book, like “likely ejecting at least a few berries into orbit,” and “a roaring ocean of boiling jam.”)

But in less fanciful scenarios, non-satiation describes what people do pretty well. People take free things they don’t need all the time, and they’re not usually offered mountains of blueberries, so economists are currently on solid, non-blueberry covered ground in making this particular assumption.

Non-satiation doesn’t necessarily seem like a bad thing - more is better, right? Unfortunately, people’s desires for more are often almost completely divorced from how much they already have. If you make $150,000 a year, you’ll probably want a 10% raise just as much as if you make $50,000 a year. That would be great, if people were significantly happier every time they got more, but at some point, the benefits of more money start decreasing, even if it never turns negative. Richard Easterlin called this a paradox: even though people are happier to have more money, as wealth increases over time, people don’t get (much) happier.

Needs and Wants

When we have what we want, inevitably, we want new, more, or different things. The late Tibor Scitovsky, an economist who worked on understanding the relationship between what people get and how happy they are, suggested that there are two different things people want: comfort and stimulation. This was intended to explain why people wanted more money - eventually they run out of needs, and start working on desires for stimulation instead.

Maslow’s famous theory of a hierarchy of needs lays out a similar idea, in more detail. People first try to meet their basic physiological needs, such as air, water, food, shelter and sleep. Once those needs are fulfilled, they move on to safety, such as making sure they are healthy, and they have enough money to meet their needs in the future. Next they pursue social needs for friendships and intimacy, then move on to self-esteem and self-actualization. At least that’s how the theory goes.

Unfortunately for Maslow’s theory, at least in the simplest form, people don’t actually pursue needs in any single universal hierarchy. People often neglect physiological needs in pursuit of self-esteem and self-actualization - they diet to look good, sometimes far past the point of health. In other cases, people seem unable to move past their physiological needs, binge-eating and using drugs, sometimes past the point where they are able to fulfill even other physiological needs. For example, there are drug users on the street gave up shelter for drugs, and some people who overeat to the point of making themselves unable to care for themselves.

Maslow could say that this isn’t much of a criticism. He was talking about the hierarchy of needs for well adjusted people, and a theory of healthy minds isn’t about people who are, in some sense, broken. But it turns out that even among healthy people, there is significant variance in what they value, and what they prioritize. But before talking about differences, it’s worth going back to Scitovsky’s dichotomy of needs versus stimulus - because a useful way of understanding motivations generally is looking at where they fail.

Making Bad Decisions

Edgar Allen Poe had a succinct explanation for bad decisions: it’s the Imp of the Perverse. Even the worst decisions are advocated by this imp, whispering in our ear to do stupid things. See a fire? The imp tells you to put your hand in. Stand near a cliff? The imp is telling you to jump.

But even if we dispense with Maslow’s unreasonable claim to only care about healthy minds, very few of the bad decisions that we make are of the type Poe is discussing. Sure, you probably occasionally do have a small part of your brain that tells you to consider actions you know are straightforwardly harmful. But most bad decisions are far more prosaic - we overeat, we don’t answer an email because it’s annoying, or we delay finishing a Substack post because we got stuck on what to say next.

There are several different explanations for why people make bad decisions, and they each have something useful to say about cooperation. We’ll consider four of them: automatic responses, stimulus seeking, internal mental conflicts, and unstated or unconscious motives.

Thinking fast and executing adaptations

One reason we do things that aren’t good for us is because we’re usually not pursuing goals. Instead of trying to achieve something, our brains are on something like an autopilot. Daniel Kahneman calls this “thinking fast,” and his description, which is largely based on “recognition primed decision making,” provides a partial explanation - people’s brains pick actions almost without a person’s awareness, rapidly, based on quick heuristics. These aren’t always simple decisions. We’ve probably all driven to work while paying no attention to the route we took, driving basically automatically. And if you’re anything like me, you’ve gotten off the couch, walked to the fridge, made yourself a bowl of ice-cream, and eaten it, all while only paying attention to the radio, the TV, or a game on your phone. It wasn’t a good decision.

In this model, our brains are at least sometimes lazy. The human brain has limited capacity, and it can’t always be doing everything. To save energy, or when distracted, or when under pressure, people default to just doing the thing that comes to mind first.

The default to simple reactions might be great. For example, a baseball player at bat needs to react more quickly than a rational analysis allows to decide whether to swing or to wait for a better pitch. A wrestler or a martial artist similarly reacts almost instinctively to a situation, where their “muscle memory” has them act or respond far more quickly than they could decide if they needed to analyze the situation. Malcolm Gladwell wrote an entire book about the virtues of such “thinking without thinking,” and how it can be used. Art experts that can instantly tell if a painting is a fake, speed chess players can recognize and react to a position without analyzing it explicitly.

Of course, sometimes this mental laziness and automatic response has a cost, such as when people less athletic like myself instinctively flinch away from a ball they are trying to catch, or far worse, when drivers automatically swerve away from an animal in the road right into oncoming traffic. And in Blink, Gladwell also points out that this is where biases can show up, so that police at least sometimes react in racially bias ways when confronted with potentially dangerous situations. Even in situations where time is available, quick reactions embed biases, so that blind auditions remove the automatic gender biases in orchestral auditions.

This doesn’t really describe the imp of the perverse, but it does describe why we so often fail to do the smart thing - it’s because our brains can be on autopilot, and the smart thing never occurred to us to try.

Superstimuli

A second explanation for at least some bad decisions is related, but is due to a different type of poorly adapted behavior, of seeking “too much” in a certain sense. Tooby and Cosmides point out that evolution has goals, but those goals aren’t shared by organisms. Evolution favors species that have babies, while people just like sex. Evolution favors species that find and consume calorie-dense nutrition for energy, but people just like sugar and fatty foods. Chocolate ice cream won’t help me nutritionally, and extra weight certainly doesn’t help my health, but I eat it. Why? Because it tastes good, and I didn’t stop to think twice. All of these stimuli are fulfilling my goals in ways that are unrelated to the evolutionary goal which created them - but as the examples illustrate, the stimuli are pursued farther than needed to fulfill the goal.

On the other hand, Maslow posited that people move past basic needs towards higher levels of self-actualization. And self-actualization is not just stimulation, much less overstimulation, it’s something new. It’s something that you reflect on, and hopefully it improves who you are. But when I reflect on my goals, I’d really rather lose weight and read a book than eat ice cream in front of the TV. Or at least, that’s what the thinking part of my brain tells me.

This again is not an imp of the perverse, it’s my brain moving past my rational decision-making mind, and making its own decisions. In fact, my unthinking, fast-acting brain wants stimulus, not self-actualization. People’s fast-thinking brain likes stimuli. And people don’t just like them, they chase them far past the point of actually achieving their initial goal. How often does a person sit down to watch a single episode of a TV show just to relax after work, and look up hours later having binged-watched an entire season? This doesn’t fulfill a need - or even provide a stimulus that achieves a higher-level goal in Maslow’s hierarchy. Instead, really compelling television hijacks the stimulus-seeking part of a person’s brain. Perhaps these stimuli provide a simulacrum of social needs, but not in a way that Maslow would have approved of as a step towards actualization.

Our fast-acting, stimulus seeking, autopilot brain can be sated, perhaps, since there never needs to be a moment of calm in our hyperactive, always-on world. In the modern world, there is always something interesting and new to learn, to experience, or to listen to. We can hyperstimulate anything, even feelings of self-actualization. But in the modern world, this isn’t coincidence, it’s design.

Akerlof and Shiller, Nobel Prize winning economists, argue that the modern economy is geared for exactly the right things to create and provide superstimuli. Companies are more profitable if they can hijack people’s brains, rather than provide value that aligns with people’s longer term goals. And this looks a lot like exploitation, rather than providing value to customers. As we’ll discuss in later posts, this is a failure on multiple levels - in our context, a failure to accurately predict what will make us happy long term - but the failure is due to a business strategy which is a failure of cooperation at a different level as well. That’s because, as I hope to talk about in a future post, unfulfillable desires, and maximizing something indefinitely, make cooperation harder.

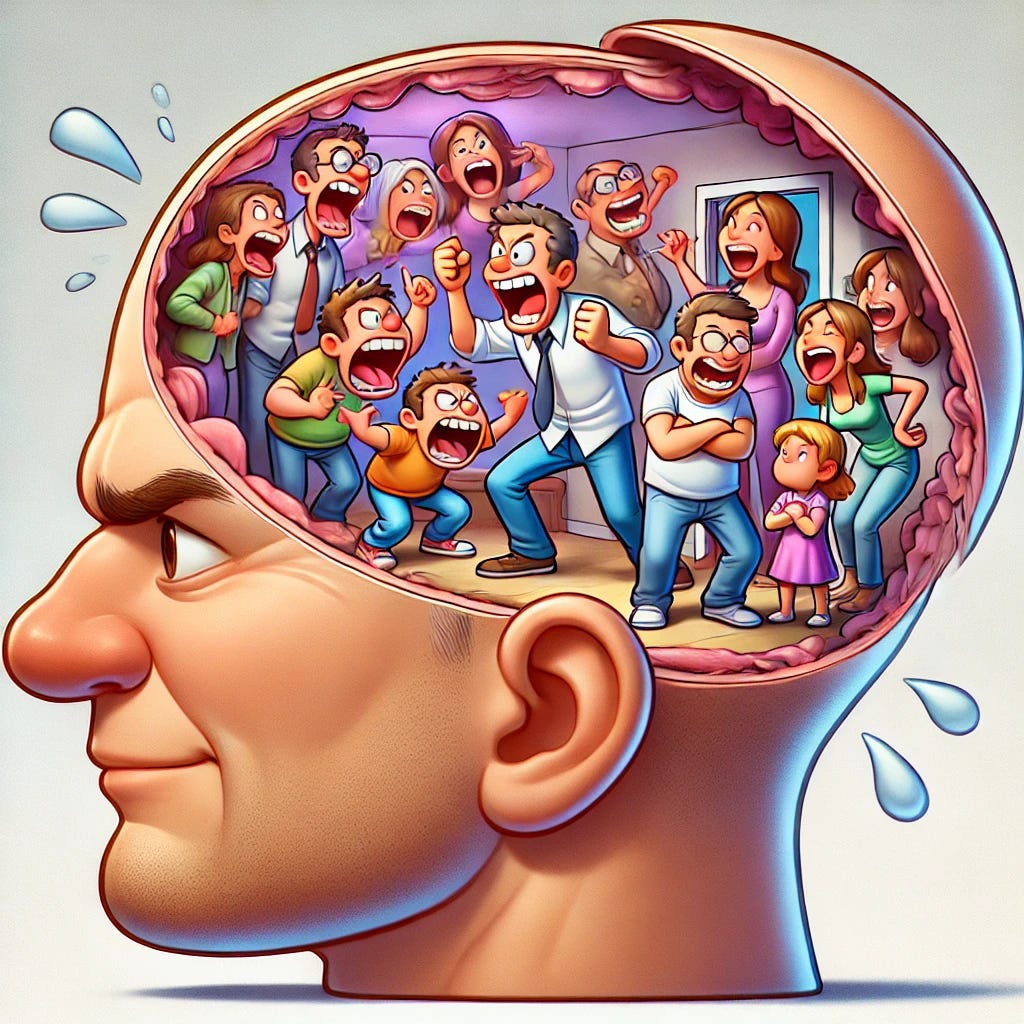

Internal Family Systems

The next of our four explanation of how we make bad decisions, or fail to act rationally, is psychological rather than evolutionary, or economic. In 1980, Richard Schwartz had just completed his PhD in marriage and family therapy, and was working as a family therapist. One early client, a young woman, came to him with a problem - she would routinely binge on food and then force herself to vomit. At the time, bulimia, a psychological and medical issue involving people overeating and then purging by vomiting or use of laxatives, had only recently been given specific diagnostic criteria. Schwartz was interested in figuring out how family therapy could help. To test this, he approached Mary Jo Barrett, who was interested in eating disorders, and they ran a study on whether family therapy could help with such eating disorders - but it was unfortunately only marginally successful.

In the following years, he explained, he continued treating some of the women, and realized that instead of their bulimia being due to social or family pressure, those suffering described competing and contradictory impulses. One described different parts of their personality with “warring parts,” in some cases having distinct voices, almost as if they had multiple personalities - itself a potentially worrying sign. But in the course of therapy, he found that many people with bulimia described similar, if less explicit, warring urges.

But Schwartz was not a psychotherapist, he was a family therapist, so he used the tools he knew - trying to understand the roles of the different “people” involved in the conflicts, and working to resolve them. Often, it turned out that dangerous or self-destructive behaviors were one internal actor that was upset or scared about something. In response, that aspect of the personality used self-destruction as a tool to maintain control. This behavior was not the entirety of the person, however, and for bulimics, one internal actor was hungry, and went to eat food. This was seen as threatening to the fearful actor, which was, in many cases, afraid of weight gain. The fearful actor would become upset, and then assert that the only way to fix the problem was purging, and they would impulsively assert control. This cycle would then repeat, and eventually become a pattern. This pattern led to people making decisions that they didn’t actually endorse - they couldn’t stop themselves from making the same bad decisions over and over again, so they were seeking treatment.

To Schwartz, this sounded remarkably similar to the cycle of abuse in families, where a child is exposed to abusive behaviors, and decades later, as a parent, adopts the same role with their own children. And this was something he knew how to address - build trust with each actor, find ways to address their conflicts or avoid the situations where they would arise, and rebuild trust and healthier relationships.

Based on this, he developed a system of psychotherapy, the internal family systems model. Perhaps surprisingly, this worked very well. So well that in the decades since, many have adopted this model for a host of different therapy applications. And it turns out that in the decades since, people have found that many people, even those without any obvious psychological issues, have similar internal dynamics, with different internal actors wanting different things. As we’ll see in later posts, groups of people who have individually rational goals can collectively act incoherently. So in addition to being a useful insight for people interested in their motivations and trying to address their own needs, the internal family systems model is a possible explanation for why people end up with incoherent goals and desires.

True Motivations and Elephants in Your Brain

Lastly, we can look at a different internal inconsistency - which is that peoples’ actions don’t match their stated motives. Sometimes this is a kind of accidental revelation of bias, but sometimes it’s because what I “really” want isn’t the same as what I think I want, much less what I tell others. And this isn’t (always) due to competing parts of my mind. For example, I sometimes tell people I’m tired, or busy, to get out of social obligations - shocking, I know. But it’s not only about lying. When asked, I sometimes say that I’d prefer a vegetable platter to a candy bar, and even eat the vegetables, when I know that I’d really prefer to seek stimulus and just have the candy. I haven’t only lied, I’ve actually changed my behavior to do something that isn’t what I “really” prefer.

Kevin Simler and Robin Hanson wrote a book that says we don’t realize our true motives, even though they make sense. They suggest that most decisions people make are guided not by their stated or even conscious motivations, but rather by basic desires which they don’t mention or even notice. These proverbial elephants are things like prestige, or feeling cared for - and it seems like on some level, we know this, even if we don’t admit it.

Children often make this obvious when they ask for things that don’t “really” help them. Probably 90% of band aids used in my house, and the houses of most of my friends with kids, are for injuries that are not bleeding. Sometimes, the band-aids are not even on their skin - they go on over their clothes. Why? As a parent, it is clear that they want a band-aid on the bruise as a symbol that someone cares for them; the actual use of a band-aid, stopping bleeding, isn’t relevant, but it requires parents to do something actively to address the pain. And adults do the same thing - they often go to the doctor to feel cared-for, even when they know there’s nothing a doctor can do. (So it’s no wonder that the demand for medical care keeps expanding - it seems to be one of the truly non-satiable goals people have.)

Does this mean that what people truly want is the unstated motivation, the one that they aren’t even consciously aware of? I think that’s what Robin Hanson argues, but I’d instead say that it means that people are complex, and often choose stimulus or behave according to motives they don’t fully understand. There’s no need to say that their “true” values are either the ones they state, or those they display publicly, or the ones that guide some of their unthinking behavior, any more than we’d say someone who smokes actually wants to die young. That is, people’s behavior isn’t always a guide to their beliefs or their values - and when they conflict, any decision that is made is bad according to at least one of the two incompatible sides.

Incoherence, Cooperation, and What Lies Ahead

Now that we’ve laid out a few theories for why it happens, we need to get back on topic - cooperation. And to get there, I will note that despite the various incoherent parts here, people are mostly making reasonable decisions, and aren’t completely incoherent. So regardless of whether we think people are lying to themselves or to others about what they really want, or are just having trouble making the decisions they’d want to, they do have preferences. And while in the above section, the noted selfish, short term, incoherent, or subconscious decisions tended to undermine cooperation, that partly reflects my bias in choosing examples; there are certainly times when the mentally lazy or intuitive choice is to cooperate instead of defecting.

In either case, the gap between beliefs and behaviors, or between bad decisions and true goals, can be important because “real” motivations can allow cooperation even when claimed motivations do not, or vice-versa. Any cooperation, which a previous post defined as requiring mutual benefit, needs to better fulfill those often incoherent and sometimes self-defeating preferences. And this all adds up to a question about how we think about scaling cooperation, which we talked about in the previous post - but in this case, it’s not just from people to groups to societies, it starts with people’s internal cooperation.

With this framing, it’s clear that the differences between what people actually choose, and what they say they want, are vital to making cooperation between humans work, and scale. For this reason, Robin Hanson has said that a critical challenge for policymakers is figuring out ways to fulfill people’s true goals while stating they are fulfilling their stated goals, to minimize the tension. I think that’s partially right, if overly cynical. At the same time, I think it reflects something akin to an internal family systems model, where cooperation needs to occur between people’s internal actors to enable cooperation more broadly.

So we’ve seen that people have incoherence, and despite that, as noted in earlier posts, cooperation is both common, and on a sound theoretical footing. But to foreshadow on point I will talk about in later posts later, in practice, almost all cooperative systems are also at least somewhat incoherent. People are often incoherent, companies are imperfectly internally aligned, countries are a mess of internal politics, but in each case, they can cooperate. And I’ll note that the incoherence of current LLMs - whether reflected by their occasionally inconsistent internal models of the world, their schizophrenic personalities that can depend on their prompts, or the differences in how they are built - seems parallel to human diversity, both internal and interpersonal. So not only does the existing panoply of actors, and amalgams of actors, matter for cooperation, but the diversity of possible minds, and the set which end up created, may be critical in determining whether cooperation can and will occur.

But before we get there, we will need to look at next is what types of goals are compatible with cooperation. So in the next post, we’ll dive into which types of goals can allow cooperation, and which cannot, and what happens when these individual wants meet in a shared environment.